The evolution of co-living

Student housing’s emergence as a recognised property sector is supporting the development of co-living.

In fact, the growing co-living sector can be understood as a development of student housing and this has implications for a number of Asia Pacific markets. Total investment in student accommodation was $17.4bn in 2018, the third year where volumes exceeded $15bn.

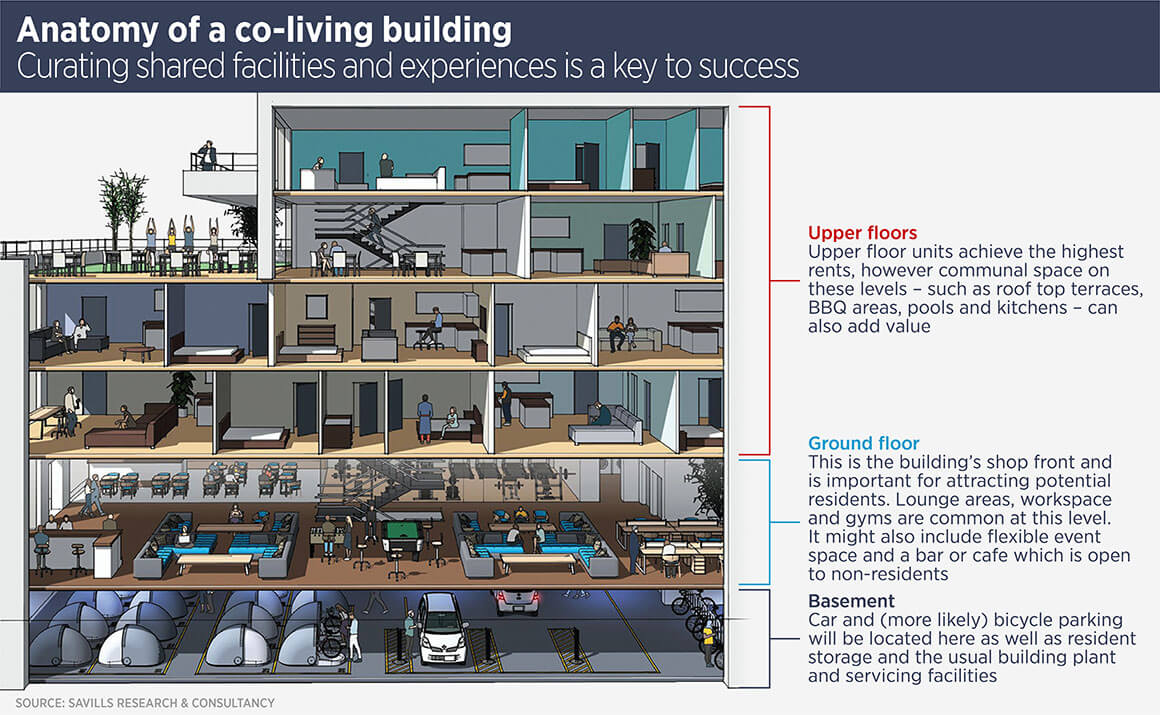

Co-living developments typically provide rental apartments which are smaller than average, but with the addition of shared spaces, which might include kitchens, a screening room, a gym and workspace. The building operator will often provide shared practical and social services, from managing cleaning to organising social functions.

Paul Savitz, director of student accommodation at Savills Australia, describes both co-living and student accommodation as “a shift in the housing journey” between living with parents and owner-occupation.

Graduates who have grown used to purpose built student accommodation (PBSA) will increasingly prefer co-living as their next step, rather than a traditional flat share or returning to the family home. “Co-living offers private living space alongside better facilities than flat shares or family homes can offer, as well as the opportunity for wider social interaction.”

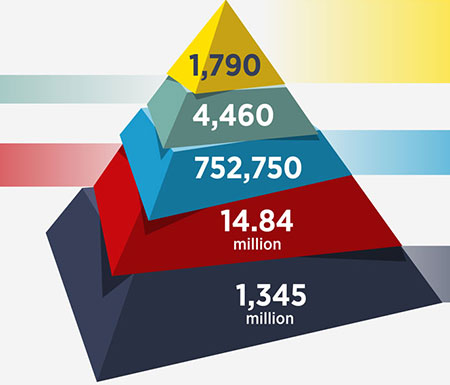

Savills analysis found 1.46 million 25-34 year olds rent across Australia. Nationally over 250,000 25-34 year olds live alone and 18.7% of 25-34 year olds also earn above the national average income, making them ideal prospective tenants for high quality co-living properties.

Anecdotal evidence suggests co-living properties in dense urban centres are typically home to young professional residents from either start-up, creative, financial or professional sectors.

“Housing affordability is a key driver of this market,” says Savitz, “but that is not the whole story. There is a preference in this demographic for experience over ownership and a desire for flexibility. Young professionals are more mobile, both nationally and internationally, than ever before.”

So far the Australian co-living market is fragmented, but Savitz expects consolidation in the future, as happened in the student housing market, which is now dominated by a small number of groups, often operating internationally and backed by global capital.

“The model and the buildings are very similar. It wouldn’t surprise me to see student accommodation providers move into this space, albeit with different branding,” says Savitz.

Data on returns is sketchy, but Savitz estimates a stabilised co-living property would yield 5-6% in Australia, with Sydney and Melbourne being the most popular cities.

Elsewhere in Asia Pacific, young graduates are more likely to live at home than their counterparts in Australia, the US or Europe. Nevertheless, co-living is emerging as a sector in Hong Kong, Singapore and Tokyo, with local operators such as Weave and Hmlet growing their footprint. Both Hong Kong and Singapore have growing purpose built student accommodation sectors and severe constraints on housing. International and domestic student numbers are growing in Tokyo and the PBSA market is attracting developer interest.

In the future, India has enormous potential for co-living and new brands are emerging, mainly focused on lower-end accommodation for recent graduates. India’s government is keen to grow its higher education industry and to attract overseas students, which would support the development of student housing and co-living.

Further reading:

Savills student accommodation and co-living report

Contact Us:

Paul Savitz